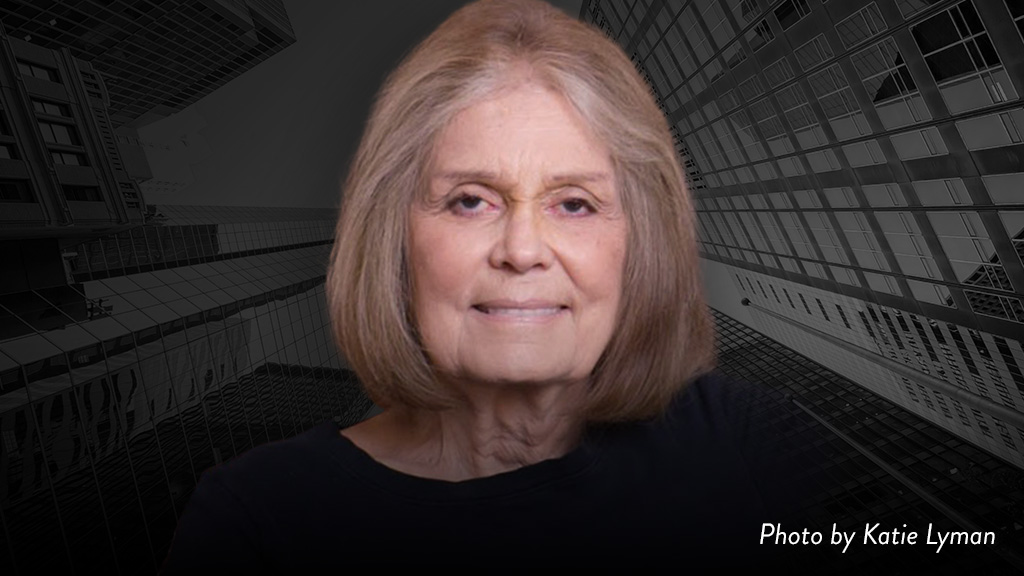

Gloaria Steinem

Writer, Lecturer, Political Activist, and Feminist Organizer

Find out what Gloria Steinem, one of the foremost leaders of the women’s rights movement, has to say about an equitable future.

I recently enjoyed a rare, in-person interview with Gloria Steinem. Gloria is a writer, lecturer, political activist, and feminist organizer best known for pioneering the women’s rights movement in the 1970s. We enjoyed a wide-ranging discussion — from where the women’s rights movement is going to what she would tell a 20-year-old version of herself.

Fighting for pro-choice rights

Throughout Gloria’s life, she has championed women’s rights, including a woman’s right to choose. Her own experience partly influenced this. When she was 22 years old and working in London, she discovered she was pregnant. Abortion was illegal at that time in the UK. However, she found a doctor willing to help her, Dr. John Sharpe. Although he was risking his ability to practice medicine, he helped Gloria and told her, “Don’t tell anyone my name, and do what you want with your life.” Gloria describes Dr. Sharpe as a tremendously wise and kind man who was there for her in her moment of need, which is one of the reasons why she dedicated her book, My Life on the Road, to him.

Where is the women’s rights movement heading?

Despite the fact that the women’s rights movement has come a long way throughout Gloria’s life, it still has quite a way to go. Issues like a woman’s right to choose are still making headlines after the overturning of Roe v. Wade in 2022. Additionally, gender roles are still very prevalent in today’s society. Many believe that although women can and should work secularly, they should also be primarily responsible for tasks around the home, and men should be the primary breadwinners. Gloria, along with countless people around the globe, believes this needs to change, as it is a virtual prison for both men and women. Gloria believes that this is now changing, as younger generations grow older and begin their lives as adults.

What would Gloria Steinem tell her 20-year-old self?

While there are countless things that Gloria would want to tell her 20-year-old self, the most important thing would be that “everything is going to be okay.” Younger people tend to have fewer life experiences, which can make problems seem much larger than they really are. One of the most important things to keep in mind as a younger person is that things tend to be okay in the end. Although it’s very rare that the best case scenario will play out in any given situation, having the worst-case scenario play out is equally rare.

Want more?

I regularly get a chance to sit down with living legends, titans of industry, and people who have forever changed the trajectory of history, like Gloria. To see our list of upcoming guests, check out the Walker Webcast!

Trailblazing for an Equitable Future with Gloria Steinem

Willy Walker: What an honor. First of all, thank you, everyone, for being here. I was going on the set at the New York Stock Exchange for CNBC this morning and walked over to David Faber, who was doing my interview, and he said, “What are you doing in New York?” I said, “I'm leaving here, and I'm going up to interview Gloria Steinem.” And his jaw literally dropped. He was like, “Wow, that's so cool.” I was like yeah. I know you all will get a lot more out of Gloria this morning than CNBC got out of me on live television an hour ago.

So, Gloria, first of all, thank you. And thank you, Ted Patch, for having it that your Aunt is here. As I was doing research on you, there was a recent Esquire magazine article that said. “What distinguished her then is what distinguishes her now, she's engaged. She's not curating an image. She is not interested in legacy, her most valuable resource is time. And when she gives it, as she often does, it's because she genuinely cares.” So for all of us here gathered for this event. Thank you. Because you taking the time means that you care about what we're doing and we're very appreciative.

The other thing that I've heard you talk about, Gloria, is circles. And then, when you meet with people, you like to put everyone in a circle so everyone feels like they're part of the conversation. So to the degree that we all feel like we are in this circle here. I just thought that as I was reading how you bring people in, sit down with them, and talk to them, you create the circle. And so we're hopefully all in a circle. I'll start with my first question. Did you watch Law and Order last night as you were heading to bed?

Gloria Steinem: No.

Willy Walker: No, I thought that's what you did almost every night was you watched Law and Order.

Gloria Steinem: It's true. I am a fan of Law and Order. Yes. But no, I confess that I was watching Dance Moms. Have you ever seen Dance Moms? Well, it's young women mainly, some young men too, who want to be professional dancers. And it's this story of their lives and their trials and their leader who runs the studio. And because when I was growing up in Toledo, I was taking dancing lessons, and I thought that this was the one thing that was going to get me out of Toledo. Not very realistic. But it still has that full adventure. And it's going to take you into another world.

Willy Walker: So you moved from Toledo to Washington, DC, and did a year of high school and then on to Smith College. You just told me before we came on that your sister had gone there, and that's what brought you to Smith. As I was thinking about that. Did you go to Smith on a scholarship? How did you afford Smith, given the way you grew up in Ohio and your father leaving when you were ten and having your mother take care of you until you went to live with your sister?

Gloria Steinem: I think the first year I was not on a scholarship because my mother had actually sold our ancient, terrible house in Toledo in order to finance my way into Smith. And then later on, I did get it. But also, it was way less expensive than college has become, hugely more expensive. And I have to say for Smith that it was a good thing, socially speaking. If you were on a scholarship, if you weren’t on a scholarship, you were on a daddy ship, which was kind of looked down upon anyway.

Willy Walker: After Smith, you came to New York. And I've heard you talk about seeing a woman walking down the street in Manhattan who is dressed in an Australian coat, and you looked at her and said, “That's the first free woman I've seen.” What captured you?

Gloria Steinem: That's so interesting that you found it. That's true. She was an artist. Whose name may come back to me before we leave. And I was across the street from her, and she had no purse, which struck me as freedom. She had on a kind of big old coat that was flying out behind her. And I thought this is the first free woman I've ever seen. And I never forgot her.

Willy Walker: Did you talk to her?

Gloria Steinem: No. She was across the street. So, only later on did I understand who she was, she was an artist.

Willy Walker: And what was it at that moment when you saw that first free woman, in your view, that said to you, “I need to do something along these lines. I need to take what that made me feel like and make more women free.”

Gloria Steinem: Well, I don't know if I've thought about it then as a movement. But I think there was still in my era, the idea that you didn't find your own identity; you married your identity. And that was very strong. We're talking about the 1950s, okay? This was a very conservative time when people were consciously trying to go back to the old way because, after World War II, that seemed much safer. And my classmates, the shine of engagement rings as people raised their hands in class was blinding. Everybody was engaged. I was engaged too. And to a very good person. And somebody I continued to know all of my life. But it just seemed as if you made this one decision, you didn't have any other decisions to make after that. So instead, there was a small scholarship that somebody had left at Smith to go to India. So, I went to India instead. I don't know how to explain this exactly, but my mother and both my grandmothers had been Theosophists, which is a philosophy that leans heavily towards India. So I had some familiarity with India. And I just got on a ship and left. It's amazing what we do in our youth. Right.

Willy Walker: The Theosophists believe in reincarnation, correct?

Gloria Steinem: Yes.

Willy Walker: Do you?

Gloria Steinem: I'm open to it, but I don't pretend that I know.

Willy Walker: You are just speaking of age and reincarnation. You have a pretty significant birthday coming up at the end of this month.

Gloria Steinem: Shocking. We're talking shocking.

Willy Walker: My friend David Faber was bemoaning the fact that he turned 60 on Thursday. And I said, “You look great.” She's turning 90 in 2 weeks. Applause.

Gloria Steinem: I did my homework because I tried to find, online, the oldest woman in the world. And I did find.

Willy Walker: 118.

Gloria Steinem: No, I found a woman in the Himalayas who says she's 130.

Willy Walker: Really?

Gloria Steinem: Just saying.

Willy Walker: I tell you, I literally was invited two days ago to go to India to meet the Dalai Lama in three weeks, and maybe I can go track her down while I'm over there. So, talk to me for a moment about the rally when you said, “I have.” When you were talking about abortion rights? And you were giving the speech and you were talking generally about the right to choose. And then you insert it into the speech, “I have,” As you thought about, if you will, coming out with that in that day and age. Did you say it because you just wanted to be honest? Did you say because you needed that from a leader standpoint to, if you will, put your own personal story into the broader narrative?

Gloria Steinem: No, I think I said it because, at the time, 1 in 3 American women had had an abortion at some time in her life. And it just seemed crazy that this was not recognized. Also, I think by that time, I had visited Africa and discovered sitting with women in the middle of the Kalahari Desert, and they were showing me the herbs they used to facilitate birth, literally the herbs that were growing. The herbs they used to support…. So I suddenly realized, wait a minute. This has always been true. It has always been sometimes necessary and important for women, especially to regulate Earth. And why have we allowed various religions, or whatever, to tell us otherwise? It just seemed totally illogical. And I remember then I was also speaking with a woman named Florynce Kennedy. And this wonderful, outrageous civil rights lawyer was, and she always used to say, “If men could get pregnant, abortion would be a sacrament.”

Willy Walker: You dedicated My Life on the Road to Doctor John Sharpe. And when Doctor John Sharpe was the doctor who performed that abortion illegally in 1954, ‘56.

Gloria Steinem: ‘57.

Willy Walker: ‘57. And you write that he said two things to you. Don't tell anyone my name. And live your life.

Gloria Steinem: And do what you want to do with your life.

Willy Walker: And do what you want with your life.

Gloria Steinem: What a wonderful man. I had just been living in London, working as a waitress, trying to wait until I got a visa to go to India, where my fellowship was. I didn't know anybody maybe a couple of people. I found his name in the phone book, and he was just this enormously wise, kind person who came along at a crucial moment. Which I hope we can do for each other. People turn to us in a moment of need. I hope we can do that too.

Willy Walker: Had anyone else up until then, Gloria, given you that type of advice? In other words, was what he said that day of “do with your life what you wanted to do.” Had anyone else, had your mother, or your father said something of that nature to you or anyone else?

Gloria Steinem: Well, I have to say for my parents that they didn't say otherwise. They didn't tell me that I had to lead a certain kind of life. But they were not having such an easy time themselves. My Father had two points of pride. He never wore a hat, which is his generation. Men were supposed to wear hats, and he never had a job. He had a little summer resort in southern Michigan, and like a dance pavilion where you can dance over the water. And in the wintertime, since he didn't like the cold weather, he would put us into a house trailer. Me and my sister, the dog, my mother, and then we would go to Florida or California. Therefore, I didn't go to school. But I was reading all the time. I love to read. I was in love with Louisa May Alcott, I thought. And my mother used to say to me, “Why don't you look out the window? This or that, I would say, but I looked an hour ago.”

Willy Walker: After giving that speech where you said, “I have” there's a quote which is “Choose between giving birth to someone else and giving birth to ourselves.” Why do you think certain women react poorly to that statement? Or why do you think certain people in society react poorly to that statement? Is it threatening?

Gloria Steinem: I can't be sure. I don't know what's in their hearts when they say that. But I think that various institutions in our lives have tried to make brisk giving more important than personhood for women. But religions have sometimes done that, although I'm not sure we know the truth of it exactly because the Catholic Church actually allowed you to abort a male fetus in less time than a female fetus. They only thought that you moved by when the fetus quickened. So, abortion had been allowed, and it was only Napoleon the Third who made a deal with the Pope to declare abortion a mortal sin because he wanted more people for his armies. It isn't as if it has come down to us necessarily exactly as it happened, but it just seems to be the basis of democracy. Either we get to make decisions, men and women, over our own physical selves, or what good is democracy to us.

Willy Walker: I've heard you talk about democracy, and you say democracy isn't actually real, it's more of a hope. So, as you talk about democracy, I thought particularly given President Obama's comments about his whole image of Obama, I believe we all sit there and say that is the definition of hope as it relates to that.

Gloria Steinem: It is great. Thank you for playing that. We need him.

Willy Walker: How was that? It must have been really amazing.

Gloria Steinem: Yes. No, it really was.

Willy Walker: Absolutely up there as far as one of those life events.

Gloria Steinem: Yes.

Willy Walker: Anything else up there with that?

Gloria Steinem: Here. I'm sitting here.

Willy Walker: Exactly. That's really good. Really quick, but wrong. But as you think back on it. You've done so much. You've seen so many people. You've traveled the world. By the way, the title of your final book, Of Your Life on the Road, is that more towards your first 20 years of getting in the van with your father and your mother and packing off of being the life on the road? Or is that for the latter 70 of traveling the world and doing everything?

Gloria Steinem: It's more for traveling on my own, I think. Because when the women's movement, as we think of it now, was really beginning, there was vast interest and not a lot of support. So, I, together with a fearless woman named Florynce Kennedy, a wonderful human being, an African American woman lawyer. I don't even look her up. You’ll be totally knocked out. She was going around to speak. She suggested that I go with her because that meant if we were representing each different group, in a sense, not that we're different, but anyway, we would attract a more representative audience. So, I learned that I didn't die, which I thought I would if I spoke in public. Now doesn't that happen to you. You lose all your saliva. Each tooth gets a little land or a sweater. You can think what's coming next. Okay. I definitely had that.

Willy Walker: You also said earlier that when you get done public speaking, you always go back through it and say, “What didn't I say that I wanted to say?”

Gloria Steinem: Yeah, I always second-guess myself.

Willy Walker: Well, before I continue on my list of questions because I'm driving the conversation here. What's the one thing you want to make sure gets said here in front of this group?

Gloria Steinem: No, it's not like I predetermine the selection. So what comes up and then you think, I should have said that.

Willy Walker: In reading a lot about you, self-esteem is something that you spend a lot of time looking at and focusing on. And I think you said that women take out a lack of self-esteem on themselves. Men take out a lack of self-esteem on others. Talk for a moment about the difference in the genders and women as you fought for women's rights. How important that sense of self-esteem is for women to do what they want.

Gloria Steinem: Well, it's not like it's some evil plot. It's just that there are gender roles, and there used to be much more than there are now. And so, the idea of self-esteem was adjusted to the gender roles. So for men, self-esteem had to do with accomplishment outside the home, with earning, with having authority with however it was phrased. For women, it had to do with marriage, children, and the house itself. All of the things that Betty Friedan in her important book was trying to say, “Wait a minute, we're all whole people.” We all have ways that we want to show our worth.

Willy Walker: As you look at self-esteem, you delineate between core self-esteem and what is situational self-esteem.

Gloria Steinem: This guy has done all this research. When am I losing my memory? I'm calling you up.

Willy Walker: Anytime, Gloria. I will take that phone call. But as you think about core, I thought it was fascinating the way you analyze these two things. To summarize, what I took away from your writing on this is that if you as a child, if you don't gain core self-esteem, your parents look beyond you, or you're constantly compared to other people that leaves sort of a gap in your own core self-esteem, which in many instances for men sets them up to go try and find situational self-esteem, which is how much money can I make? What kind of car do I buy? And that gets you on sort of this treadmill of this never-ending seek for situational self-esteem to try and fill in on the core. But if you don't have the core, the situational, never fill it. Fair summary.

Gloria Steinem: Yeah. Absolutely. It is gendered. It is affected also by race, which it should not be obviously. We are intrinsically worthwhile. Each person here is a unique miracle that could never have happened before and could never happen again. And we share human qualities. We have unique talents. But because of racism, because of bias about males and females, because of economic class, we don't necessarily know that. We don't necessarily know that we are, or grow up anyway, knowing that we are each unique.

Willy Walker: That voice that you just used to explain that to us. When did you find that voice? What do you just do with my question. To take it and say it in the way that you said it is, what made you the person that you are. When did you find that voice?

Gloria Steinem: I don't know. I think we always have a voice in our heads. Even if we don't feel like we can yet say it. But I don't know. Something I think I was lucky because something allowed me to have a sense of fairness. I could have grown up in a way that I did not. I remember I don't know if this is relevant or not, but I remember being totally in love with Louisa May Alcott. Little women. And she had that sense of fairness, involvement in the revolution, in her own life. I wonder as children don't kind of have that. There've been experiments where they put two babies together and the babies, if one has a milk bottle and the other doesn't, and one baby will share it with the other baby. That we are social animals.

Willy Walker: That's for sure. But certain people have a gift for expressing for ideas and conveying thoughts in a unique way. As I think about your career and what made you the person that you are, it was that gift of being will take an idea that I just gave you. And then, if you will, translate it into something that is so compelling for everyone in the room to hear.

Gloria Steinem: I don't know. But I hope we've recorded this so I can listen to it.

Willy Walker: We are recording. Winding the clock back, what gave you the impetus for the desire to start Ms. Magazine?

Gloria Steinem: I had been a freelance writer living in New York, making a living by writing for Esquire and writing a variety of magazines. And then also, we together started New York magazine. So I realized it was possible to start a magazine. And I could see that the women's magazines, with all the goodwill of the women who were working there, were still restricted by advertising, because they had to produce articles that complemented the ad categories that they were seeking. So it meant buying particular products and raising children. It was very gendered, with maybe one little article dropped in there to get you to buy the catalog. Essentially, it was a catalog of products. So, I realized that it wasn't my fault at all of the women who worked there – it was the economic structure that they were working in, and we could start a magazine without that if we were willing to take lower salaries, and eventually, we became a foundation so we could raise some money that way. I don't know if we could just have a different kind of economic structure. We could write about women's concerns and also invite women from other countries so their voices were there. And magazines were pretty racially divided then, too. There was Ebony, there were magazines for black writers and readers and so on, and so-called white magazines. And the advertising world was structured that way, too, as to who you saw driving the car in the car ad.

Willy Walker: And you ended up having to sell Ms. and to hear you talk about that. One of the things that sort of angered you was that you had the readership, but you couldn't get the advertising to match up to go after that demographic. And it was to exactly that point. You were just saying that there was sort of an economic disconnect. You had the readers, you just couldn't get the advertisers.

Gloria Steinem: Yeah. Well, I used to go to Detroit, for instance. We used to go to try to get car ads. And, the car manufacturers would say, okay, providing you show a woman driving this car or a man driving another car because it demeans this expensive car that a woman could drive. You can’t make this stuff up. And it was just so much trouble that we eventually became a foundation, a 501(c)(3), so that we could produce the magazine and raise money in additional ways.

Willy Walker: There's a lot of talk right now about ChatGPT, the artificial intelligence company that was set up as a nonprofit and now has this massive valuation of $800 billion or something like that. And there's a big dispute going on with Elon Musk about the original purpose of setting up ChatGPT to be a nonprofit. And then now it is turning into this very significant for-profit enterprise.

Gloria Steinem: That's interesting. I didn't know that. Did you know that? Whose side should we be on?

Willy Walker: Whose side should we be on that one? I think the issue there is that Elon Musk is unlikely to wage this fight because he thinks that he's entitled to money. He's got a lot of money. He doesn't need more money. I think he thinks that Sam Altman, who started the company, is not being true to its original mission, to set it up as a nonprofit and keep it as a nonprofit. But I don't know. The final thing I'd say on that is Elon Musk's desire to make more money though, he just went back for another pay package from Tesla that is just outrageous. And you're sitting there going, you're the richest man or arguably one of the richest men on the face of the planet, and you're still going for another incremental dollar. So that actually leads me to my question to you.

You have talked about going up to the Harvard Business School and teaching a course on how much is too much money. Talk about why you think that course needs to be taught at the Harvard Business School.

Gloria Steinem: Well, what's the point? The point is to be able to be safe, use our talents, take care of our relatives, and have children if we want to. But at a certain level, it just gets to be meaningless. Just utterly meaningless. And also, how can you hand that much money and walk around and look at people begging in the street, as we do here in New York and other rich American cities? And find that's okay. It's just not interesting. It's much more interesting to help somebody and see their talents and see them grow and see it's way more interesting than the numbers in your bank account.

Willy Walker: There you go again. That gift she has. She takes an idea and just says it in such a compelling way.

Gloria Steinem: No, I don't think that's crazy.

Willy Walker: So you said, “Have a family if you so desire to have a family.” You didn't have children. Is that a regret?

Gloria Steinem: No. I used to try to get myself to regret it because I thought it was supposed to. But I think that's probably for a series of reasons. And that may be somewhat different. For instance, when I was growing up, my mother was not well. My parents divorced when I was about nine or something. And so I was looking after my mother. And I noticed that in people whose parents had been invalids or alcoholics or, for some reason, as children, we've been looking after grownups that you don't want to do that again. It's not fair because a little person looking after a big person is not like having children, but it does affect you.

Willy Walker: You mentioned earlier that you were engaged early, and then you decided to wait until your late 60s to get married to David Bale.

Gloria Steinem: Yeah. We didn't wait to get it. We never would have gotten married, except that he had been born in South Africa and he was about to be deported.

Willy Walker: I hadn't heard that part of the story.

Gloria Steinem: Why at that advanced age? We didn't, we loved each other. We were together. We didn't have to get married. However, it did turn out to be very important because when he was very ill and in the hospital for a very long time, I could legally make decisions that I otherwise would have maybe had a harder time with.

Willy Walker: What's it like to have Batman as a stepson? So to anyone who doesn't know Christian Bale, her late husband's son, is an actor and played Batman in the last three Batman films.

Gloria Steinem: Yes, but he's a much better actor than Batman. And he's a great character actor. He's able to be a leading man, but he totally can do absolutely anything. By the time I met him, he was grown up. He was with the woman he then and later married. It was just like having a bonus friend, a really good, smart, talented guy who was secretly shy, which I think is true of actors. So often, they have to become someone else.

Willy Walker: Talking about true friends. Talk for a moment about Wilma Mankiller and your friendship with her.

Gloria Steinem: Well, Wilma Mankiller is the chief of the Cherokee Nation. It's such a loss when I think about her because she should have been president. She was so wise. And remember, what we think of democracy in this country didn't come from arriving Europeans who were imperialists and monotheists. It came from the Native American culture, which really had, from the beginning. And we don't know when the beginning was, invented their own democracy. So the chief or what we call a chief might be a man, but he was chosen by the female elders, and it was all about balance. Balance with nature, balance with internal power. And this resource is still there. We can turn to it.

Willy Walker: And another friend is Amy Richards. Why's Amy Richards the smartest person you've ever met?

Gloria Steinem: I wish she were here so I could embarrass her. I was writing, I had forgotten which book, and I was just way overdue. There was a woman helping me with research who wanted to go to Smith College, and I said, okay, I will help you get into Smith College if you replace yourself with somebody else to do the research. And Amy was the person who was still an undergraduate, who came in my door and changed my life. I wish you were here so I could embarrass her. She's the smartest person I know. She is just and balanced and just amazing. I think the great luck of my life. We have chosen families as well as families.

Willy Walker: When you think about what makes you. I heard you once say that if there was an Olympic team for functioning, I'd be an all-star at functioning. You're a lot more than someone who just functions. What is it that makes you tick if you will? What does that mean functioning is great, and I love that you'd be a starter on the Olympic functioning team. But there's a lot more to Gloria Steinem that makes you so unique. What is that?

Gloria Steinem: I don't know. I think we can see that in ourselves. I don't know exactly. I think I was lucky to grow up first with loving, kind parents who let me be who I was. My mother always said that each baby was like a person from another planet and had to just wait until you could see who they were, and you could help them to become who they all already were. That's pretty great of a parent. This country, Trump, to the contrary, is a democracy. And we are better able to become ourselves than in many other countries. I lived in India for two years, and I saw a whole different culture. And I can't put together all the happenstance, but whatever it is, I'm so glad that I am at this moment in this room with all of you. We don't know each other, but we kind of think we know each other. And I don't know what, dreams and wishes and anger is important to what is in you right at this moment. But whatever it is, because we are together now, it's gonna happen. Because we are here supporting each other in that way. We, as human beings, need to be together. The reason that solitary confinement is the worst punishment all over the world is that we are communal animals. We need each other. So however it is that you are doing this at this meeting, I say “It's fantastic.”

Willy Walker: If I were smart, I'd end up sitting right there, but I've gotten more minutes, and I don't want to miss ten minutes with you. You talk, Gloria, about that sense of link, of being linked to one another. And rather than being right. And talk for a moment about how important that concept of being linked to one another, rather than ranked against each other, is to you. Because I've heard you talk about it numerous times as something.

Gloria Steinem: Yes. We made bracelets that say, “We Are Linked Not Ranked.” It's just helpful, and I think it's a realistic concept. Because if we are told that we are ranked, then we are constantly obsessed with where we are in the ranking and getting to the next one, and so on. We probably are distracted from trying to express what is unique to us and the talents we have and so on. And we are communal animals. As I was saying, “The greatest punishment all over the world is solitary confinement because we are communal animals.”

Willy Walker: And where does the women's rights movement go from here?

Gloria Steinem: Wherever it ******* well, please.

Willy Walker: Yeah, but who leads it? That speech that Amanda Gorman gave during President Biden's inaugural.

Gloria Steinem: Yes, that was one. was just breathtaking.

Willy Walker: It's just breathtaking. Eyes on someone like Amanda Gorman to be the person who steps in. Or is there somebody else out there that you see who can take the mantle from you and carry it forward?

Gloria Steinem: I don't have a mantle. I mean, there are folks, here we are. There are people everywhere. Men are feminists and can and should be. I think we are struggling, all of us, with gender roles because then, theoretically, women are supposed to be more at home taking care of domestic things. Men are supposed to be out there earning money. This is a prison for both men and women. We ought to be able to do what it is that expresses our talents and our needs and not have these roles handed to us. And I think, in a way, the pandemic helped a bit because more men were home with their kids, and more men were at home, period. And, of course, men love their children, too. And it began to change a little bit, the hierarchy in the home.

Willy Walker: “Talk about hate and love in the sense that hate specializing and love generalizing.” I heard you say that. I thought it was such an impressive way to sort of think about what hate does in our world and what love does.

Gloria Steinem: Yes, I think Robin Morgan, a great poet, is the person who originally said that. But it is true that love specifies, and to hate, you have to import a preexisting idea of the person or the group or something in order to hate. As I was saying, “Each of us in this room is a unique miracle. You could never have happened before in exactly the same way. It could never happen again.” And that is so interesting and exciting and precious and helpful in figuring out how we can support each other. Because sometimes we see it in each other when we don't see it in ourselves.

Willy Walker: I heard someone ask you what you would tell your 20-year-old self. And your response to it was, “One, it's going to be okay. And second, enjoy it because you have no idea what’s coming next”. When I hear you say it's gonna to be okay that led me to believe that there were times when you didn't think it was going to be okay.

Gloria Steinem: Yeah. Absolutely. When I was in Toledo, my mother and I were living alone. We were living in a house that had once been a family farmhouse, but by then, was falling into the huge highway in front of us. My mother was ill. I don't know, it just felt very limited. I was in a state of unrealism that made me think that the answer was that I couldn't dance my way out of Toledo. And so I was taking a dance that I was never that good.

Willy Walker: But did you continue to dance for most of your life?

Gloria Steinem: Yeah. No, I love to dance, but my dream was to be a Rockette.

Willy Walker: Really?

Gloria Steinem: Yes.

Willy Walker: I'm sure someone can get you across the street. It's pretty close to here. Did you ever feel threatened?

Gloria Steinem: I just say that because I think show business is to women what sports is to men in poor neighborhoods. You kind of see it maybe as a way out.

Willy Walker: Did you ever feel threatened?

Gloria Steinem: Threatened.

Willy Walker: When you were an activist, speaking, traveling the world, espousing what you were espousing. Did you ever feel either physically threatened or threatened by a countermovement to what you were saying?

Gloria Steinem: Well. Not in a personal way. Not that was singling me out, but certainly, when I was living in India, I was with a group of people walking from village to village because there had been caste riots. And so this group was trying to tell women and men in villages that actually people cared about them. It was going to be alright. So on. So, I could see what people were realistically afraid of. But I could also see that there were people walking to villages saying, no, it's going to be okay. Just that there was this instinct, and it's what gave me the understanding of the importance of social justice movements because I had never seen one in that way until I was living in India. So it made me understand how important the movements were when I came home.

Willy Walker: I want to end on an excerpt from the Esquire article that was just written on you a little while ago, where the writer said to you, “I hope you understand the impact that you've had on the world and how much the world has changed because of you.” And in typical you, I think we've all seen over the last hour what you were like you said. “I guess I'll have to think about that a little bit.” And I find it to be so commendable how, not only self-deprecating, but just that you are an iconic leader, and you made such an impact on our world. And yet you would sit there with a writer and say, “I got to think about whether it actually had an impact.”

Gloria Steinem: Well, we don't know. Every once in a while, I go outside my door. The other guy who delivers the mail is there. He turns out to be the political leader of Queens. We organize something of this. It has to do with the moment, the person, and the results that you see, it’s enormously touching. And maybe we should meet again next year. And we can all tell each other what if anything changed because we were here together today. Or if you may have gained the confidence to do something you wanted to do or thought of, we want another speaker, a different speaker, next year.

Willy Walker: We'll take you back to the second Gloria, let me just tell you that. Honestly, it's a true pleasure. On behalf of everyone in the room, thank you so much for joining us.

Gloria Steinem: No, I thank you.

My Life on the Road

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.

Gloria Steinem is one of the most influential voices of our era. In preparation for having the honor to sit down and interview her, I read-up on her fascinating journey in My Life on the Road. The only thing better than sitting down with Gloria and getting answers to my questions is getting a sneak peek at life through her lens in this bestseller.

Related Walker Webcasts

Shaping the Future of Luxury Living with Jeffrey Soffer

Learn More

December 17, 2025

Leadership

CEO Masterclass

Learn More

December 10, 2025

Leadership

Emerging Trends in Hospitality with Chris Nassetta

Learn More

November 26, 2025

Leadership

Insights

Check out the latest relevant content from W&D

News & Events

Find out what we're doing by regulary visiting our News & Events pages